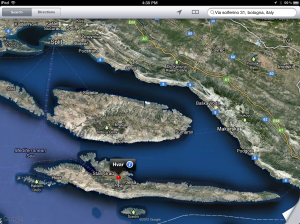

WHO KNEW? This hard-for-an-English-speaker-to-pronounce island is a hidden gem! Travel and Lesiure Magazine voted Hvar one of the “Top Ten Islands in the World.” And, of course, they’re right.

(click any photo to enlarge)

HVAR HAS IT ALL—beauty (rugged, natural, and cultivated), sunshine, hospitality, history, the turquoise Adriatic, rugged mountains, lavender, remoteness, great food and accommodations—and it’s not on most American tourists’ maps yet. What’s not to love?

Hvar Island was an independent commune in the Venetian Empire from the 13th through 18th centuries, and an important naval port with a harbor protected by a string of nearby barrier islands. By the mid-19th century, with the Venetian fleet gone, Hvar had re-oriented itself towards the tourist trade, with an early tourist board, “The Hygienic Association of Hvar,” dedicated to taking good care of visitors to this suburb of paradise.

OUR HOTEL is right on the harbor, and the paved, undulating “boardwalk” runs from here past an extended array of parks; resorts large and small; rugged, rocky swimming spots (pack your surf shoes; there are lots of spiny sea urchins to step around); and compact, sandy resort beaches. In the other direction is Hvar town, which rises from the harbor to ascend the mountain topped by the Spanish fort (the architects were Spanish), “Spanjola,” which rewards a walker with a panoramic, bird’s-eye view of the town, the harbor, the nearby islands, and the sea beyond. For a few days, this is our paradise.

Hvar is not the only Croatian location whose name begins with that rough “Ch” sound: the country, to its natives, is called Hravatska, or “Chruh-VAT-skuh.” The initial sound is rather like clearing your throat, and evokes the following musical reaction:

HRAVATSKA!

(To the tune of “Maria,” from Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story)

(please do click and enlarge the photo on the right!)

Hra-VAT-ska! I’ve come to a place called Chruh-VAT-skuh!

And suddenly, I’ve found how mis-pro-nounced a sound can be!

Hra-vat-ska! Say it soft, it’s a purring kitten;

Say it LOUD, it’s as if you’ll be spittin’;

I’ll betcha can’t say it: “Hra-VAT-ska!”

That’s not meant to be distrespectful; Croatia is a strikingly beautiful country with wonderfully hospitable people and a lovely language. It’s just hard for us Yanks to pronounce, that’s all.

TO GET HERE from Dubrovnik, we motor up into the mountains above and to the North of the city. From that height, we follow the Dalmatian coastal highway Northward, between high, rugged mountains and the sheltered, coastal waterway created between the mainland and Croatia’s many barrier islands. It is stunning! The mountains rise straight out of the sea and vault high enough to isolate the inland climate from the coastal climate. Villages, towns, and cities cling to what little coastal plain there is, and to the foothills or mountains themselves.

A well-watered, fertile plain stretches before us, once we’ve ventured inland. This is Croatia’s breadbasket. and looks as if it could feed an entire country or two. Motoring through this ample proof that the rugged, coastal mountains hide highly arable land, we head back towards the coast.

WE NOW PASS through a coastal stretch of Bosnia and Herzegovina around Neum, and then back into Croatia. This stretch of inland waterway holds acres and acres of pilings and buoys marking oyster beds. It’s reminiscent of the lobster buoys that dot the rocky Maine coast back home.

Before long, we reach Split, Croatia’s second-largest city, and the site of Roman Emperor Diocletian’s ancient retirement palace. We will save a tour of this UNESCO World Heritage site for another day; Split is also the seaport where we will board the ferry for Hvar Island, our next destination.

Looking for an ATM, I stroll into the palace (does this sound like a Danny Kaye movie?), the skeleton of which has evolved over the centuries into a village or, perhaps, a borough of Split. I can see that we’re in for a substantial treat when we return from Hvar to tour the digs of the only Roman emperor ever to have RETIRED.

The two-hour ferry ride around Brac Island—known for its high-quality marble quarries—to Hvar affords us a panoramic view of Split and the surrounding Dalmatian coast, with its rugged, imposing mountains.

OUR SHELTERED HARBOR at the other end of the ferry run is Stari Grad, a short drive from Hvar Town, the island’s center of tourist attention. The drive there is spectacular, along more, narrower, coastal roads, switching back and forth along the rugged mountainsides. One has never seen so many stones—but that’s a story for later. Some of the hillsides and valleys wear a violet tint; that’s lavender—a sprig of it sprouted long ago on the island, sprung from some wind-blown seed, and, when identified, sprouted a new island industry.

Our hotel, the Adriana, sits on the edge of the town’s central marina. Our room is a marvel of space-efficiency worthy of one of those IKEA displays that demonstrates just how much can be done with 250 square feet. Within no more than that much space, our room tastefully packs all of the needed amenities, provides a door to a small balcony looking across a courtyard to the harbor, and leaves enough space for an ample kitchenette, if the hotel ever should be converted into condo-ettes.

A few floors above is an entrance to the hotel’s spa and a restaurant and cocktail lounge overlooking the marina, Hvar Town, and the surrounding hills. An sign across the marina reinforces what we already instinctively know—that Hvar, a name we’ve not yet heard from American lips, has to be one of the most fetching, charming islands in the world. Where else will you find ads that feature “Apartments & Diving” in the same breath? There’s even a Slow Food restaurant—a fitting and welcome thought.

WHILE OTHERS NAP, I take to the undulating stone walkway that follows the coast and stroll to the west-northwest, past a nearby park and then past numerous resorts, small and large, with their short stretches of sandy beach superimposed on the rocky coastline. The tourist season is on, and plenty of vacationers have come, but nowhere does it seem crowded or thronged. It’s peaceful and quiet; and the sun and salt air are very, very pleasant.

Returning to a rocky outcropping not far from our hotel and just off the marina, I stride out across the rugged rocks to a place where I can drop into the waters of the Adriatic, stepping around the spiny sea urchins that have anchored themselves to the submerged rocks in no small numbers. The Adriatic, which will stay warm into October, is still cool in early June, and wonderfully refreshing. The hot sun and welcome breeze dry me off before long once I have climbed out.

ONE OF OUR ORGANIZED EXCURSIONS takes us around Hvar Town, past the theater built in 1612—one of Europe’s oldest, and its first public theater, a democratic institution well before its time, which brought all social classes together through common access to the theater and its events.

The Franciscan Monastery, with its garden overlooking the harbor, houses a painting of the Last Supper created out of gratitude by a talented sailor who was left by a ship’s crew at Hvar to die of an illness. While other townspeople shut their doors in his face, the Franciscans welcomed him and nurtured him back to health. The grateful painter portrayed himself as a poor man lying on the floor in the lower right of his painting.

ANOTHER EXCURSION takes us through Hvar’s mountainous terrain back to Stari Grad, for a historical tour. Our guide is a young mother who not long ago decided, with her husband, to return to Hvar after earning Master’s degrees and working in professional jobs on the mainland. The pull of this gorgeous terrain was overwhelming, trumping the economic advantages of their professional careers. In addition to his job and her guiding, they both work a plot of family land, which they cleared of the ubiquitous, small stones that cover every square foot of the island, with their own hands.

As we pass through the countryside, we see the endless lines of drywalls created out of these stones, subdividing the mountain fields into a massive scrabble board of olive orchards, vineyards, and garden plots. Lavender colors portions of hillsides and valleys like violet fuzz rippling in the wind. In part, this couple returned out of respect for the early settlers of the island—including their own families—who eked out a living from this soil by painstakingly clearing the stones from any plot that would, by their sweat, become arable and productive.

STARI GRAD means, simply, “Old Town,” and this is Croatia’s oldest town — dating back to 384 BC, when it was called Pharos by its Greek founders. Alexander the Great’s famous tutor Aristotle is said to have been born that same year. The Romans called it Pharia. When the Slavs colonized it during the Middle Ages, they re-tongued it as Far, or Huarr. The current Hvar is just another half-phoneme to the right…

WHILE SOME OF OUR PARTY NAP or kick back at the hotel on a bright afternoon, I climb the hill above Hvar Town to Spanjola, the stone fort that overlooks the town and port. A series of resotrations have brought the fortress to its current sound appearance. A lightning bolt touched off a massive explosion in its powder room (that’s gunpowder, not nose powder) in 1579, apparently damaging other buildings below to the extent that many of the local municipal structures date from the years of reconstruction after the big bang.

The view from the fortress is stunning—particularly on such a sunny, cloudless, summer day.

DO STEAL AWAY for at least a few days here before the rest of the world discovers Hvar, and it comes to the terminal state Yogi Berra once described: “Nobody goes there any more; it’s too crowded!”

###

(click on any image below to begin a slide show)

- Starry Grad

- Bosnia Oyster Beds

- Neum, Bosnia

- Croatia’s Breadbasket

- Coastal Route

- Coastal Mountains

- Dalmatian Coastline

- Mausoleum/Cathedral

- Inside Diocletian’s Palace

- Split Ferry Port

- Split Panorama

- En Route to Hvar

- Coach on Ferry

- Hotel Room

- Harbor from Hotel

- Harbor Panorama

- A Winning Combination

- To Hoist a Piano?

- Hvar Common Theater

- A Top Ten Island

- Last Supper

- Franciscan Altar

- Monastery Lamp

- Monastery Prohibitions

- Seaside Monastery

- Hvar Town

- Hives & dry walls

- Hand-cleared Fields

- Hvar Hills Panorama

- Stari Grad Archeology

- Historic Stari Grad

- Stari Grad Streets

- Stari Grad Portal

- Hektorovac Monument

- Stari Grad Street

- Hotel Cafe View

- Uphill Streetcorner

- Uphill Stairs

- Uphill to Fortress

- Wall Remnant

- Fortress Walls

- Fortress Island View

- Fortress Panorama 2

- Canon over Hvar Town

- Inside the Fortress

- Panorama from Fortress

- Our Hotel

- Harbor from Fortress

- Portal in Fortress

- Narrow Hvar Street

- Praying Statue

- Hvar “Boardwalk”

- Hvar Town Marina

- Ferry Back to Split

- Split to Hvar